“It happened, therefore it can happen again: this is the core of what we have to say.”

Primo Levi - Auschwitz Survivor

Auschwitz happened. It can happen again.

On April 4, 2025, I traveled to Poland to visit Auschwitz — the most infamous site of human cruelty and genocide in modern history. What I saw there changed me.

This website is a personal account of that journey: a photographic record of what I witnessed, what I learned, and what must never be forgotten. The color photos are all mine and represent the photos I took that day combined with black and white historical photos from online research. Auschwitz was more than a concentration and extermination camp — it was the end point of a systematic attempt to erase an entire people. Over 1.1 million men, women, and children were murdered here, most of them Jews. Others, including Poles, Roma, Soviet POWs, and political prisoners, also perished behind its barbed wire.

Walking through the ruins of gas chambers, standing on the gravel paths of Birkenau, and seeing rooms filled with human hair, shoes, and suitcases, I confronted the scale of the horror — not as an abstract history, but as a deeply human tragedy.

This site exists not only to share images and reflections, but to bear witness. I believe that remembering is a form of resistance — against forgetting, against denial, and against the slow erosion of truth.

Trae Williams

The Final Solution

“To sum it all up, I must say that I regret nothing. I was only doing my duty. If we had killed all of them, the 10.3 million Jews, I would say: “Good, we have destroyed an enemy.”

Adolph Eichman - Sassen Tapes (1957-1958)

“I commanded Auschwitz until 1 December 1943, and estimate that at least 2.5 million victims were executed and exterminated there by gassing and burning, and at least another half million succombed to starvation and disease.”

Rudolph Hoss - Commandant of Auschwitz (Affidavit at Nuremberg Trials, April 5, 1946 - victims figure later adjusted)

“The Jewish question is to be solved completely and irrevocably. It is the will of the Fuhrer that the Jewish people disappear from the face of the earth.”

Heinrich Himmler - Memo to all SS leaders, May 26, 1944

In the early 1930s, Germany was reeling from economic depression and national humiliation after World War I, creating fertile ground for Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party to seize power in 1933. Once in control, the Nazis quickly established a totalitarian regime, suppressing opposition and promoting a racist, ultra-nationalist ideology centered on antisemitism. Over the next several years, Jews were increasingly marginalized through laws, violence (like Kristallnacht in 1938), and forced emigration. When World War II began in 1939, Nazi racial policy escalated alongside military conquest. Ghettos and mass shootings gave way to a more systematic “Final Solution” by 1941, leading to the construction of extermination camps. Auschwitz, originally a concentration camp, was expanded into a vast killing center by 1942, reaching its peak in 1944 with the mass deportation and murder of Hungarian Jews—when up to 10,000 people were killed there daily. This transformation from dictatorship to industrialized genocide occurred in just over a decade.

The Camps

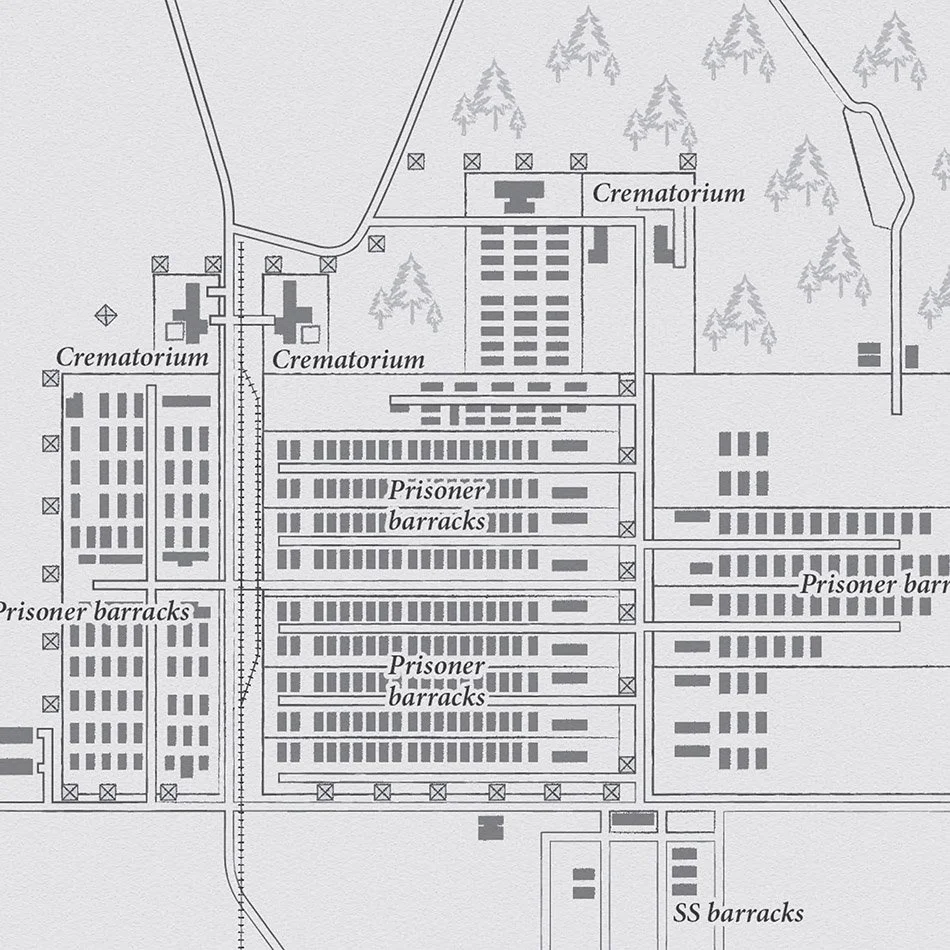

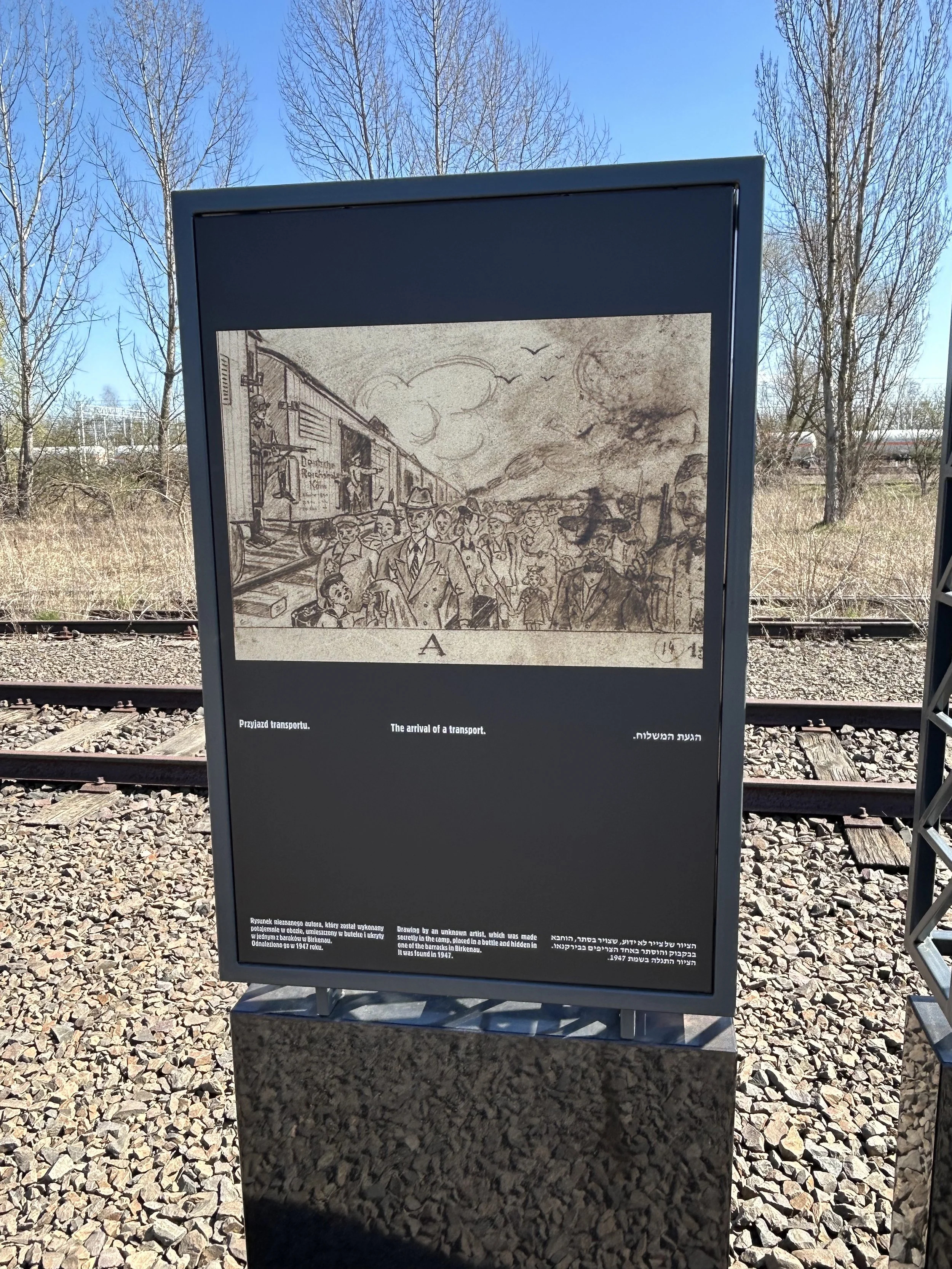

Just a few kilometers away, Auschwitz II-Birkenau was built in 1941 to handle the mass deportation and extermination of Jews from across Europe. It was unimaginably vast—covering more than 400 acres—and became the site of the largest and most deadly part of the Holocaust. Over a million people, mostly Jews, were murdered in its gas chambers.

Birkenau was designed specifically for extermination: wooden barracks crammed with people, rail lines running straight through the camp, and four large gas chambers and crematoria. It is the place most people picture when they think of Auschwitz, because it was here that the scale of the genocide became truly industrial.

Auschwitz wasn’t just one camp—it was a complex of camps that became the center of Nazi Germany’s horrific system of mass imprisonment and murder. The two main sites, Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau, tell different parts of the same tragic story.

Auschwitz I was the original camp, set up in May 1940 in the Polish town of Oświęcim (renamed Auschwitz by the Nazis). Built on the site of old army barracks, it first held Polish political prisoners and later expanded to include Soviet POWs, resistance fighters, and eventually Jews and other targeted groups. With its brick buildings, guard towers, and electric fences, it also served as the administrative hub for the entire Auschwitz complex.

This camp is where some of the first gas chambers were tested, and it was also where inhumane medical experiments—like those conducted by the infamous Josef Mengele—were carried out. While smaller in scale than what followed, Auschwitz I marked the beginning of the Nazis’ industrialized killing machine.

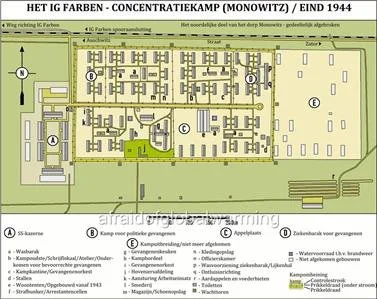

Monowitz, also known as Auschwitz III, was a concentration and labor camp established in 1942 as part of the Auschwitz camp complex in Nazi-occupied Poland. It was built to provide forced labor for the German chemical company IG Farben, which was constructing a large industrial plant called Buna Werke to produce synthetic rubber and fuel. Located about seven kilometers from the main Auschwitz I camp, Monowitz held tens of thousands of prisoners—mostly Jews—who endured grueling conditions, including long hours of hard labor, starvation, brutal treatment, and inadequate shelter. The mortality rate was extremely high due to the harsh environment and exploitation. Monowitz represents one of the most direct examples of corporate complicity in the Holocaust, as prisoners were systematically worked to death to serve industrial interests.

Auschwitz I

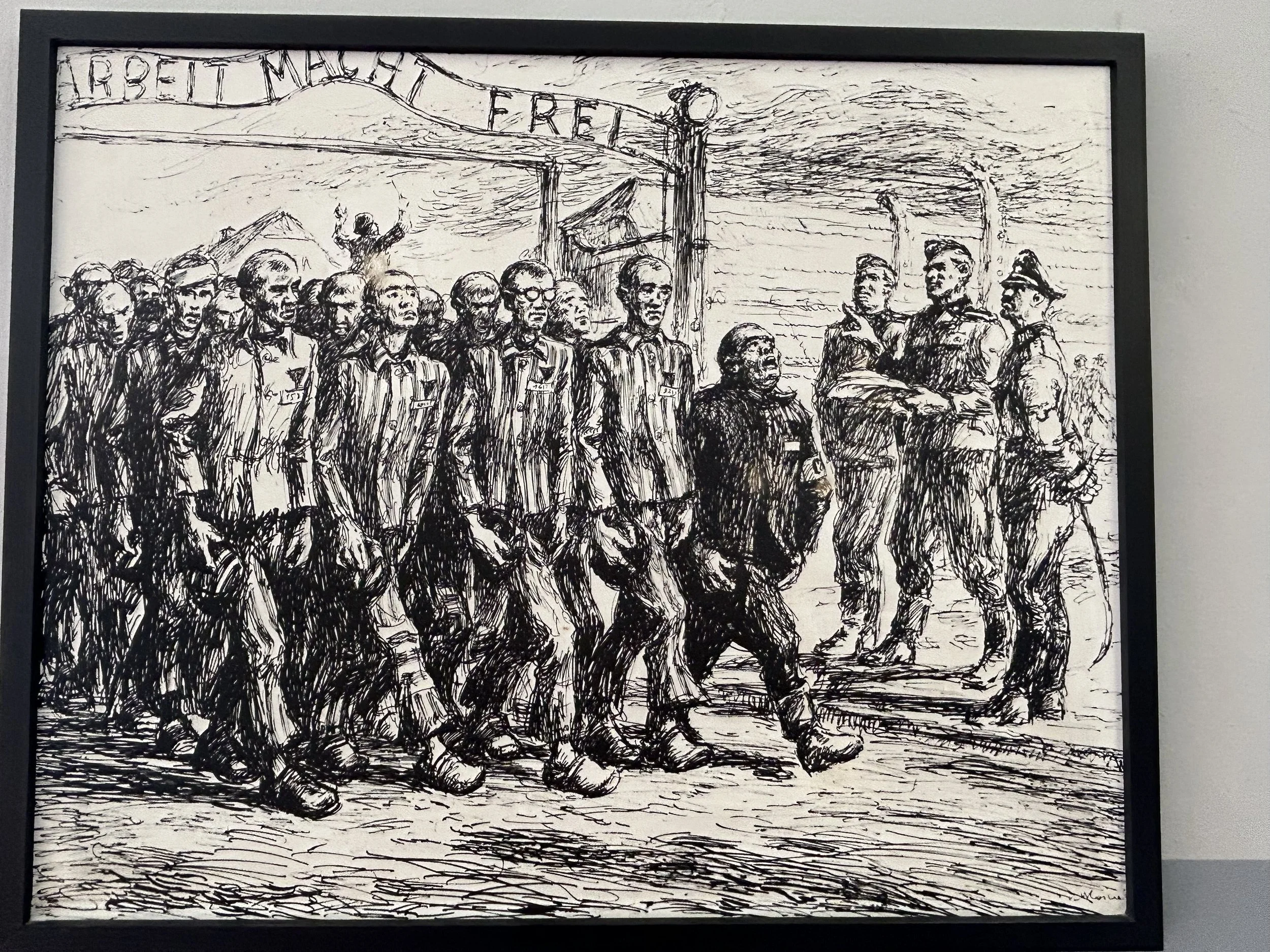

When you first enter Auschwitz I you follow the same path of new prisoners who were led through a wide courtyard bordered by brick barracks and guard towers. Electrified fences surrounded the camp, and the infamous iron gate bearing the phrase “Arbeit Macht Frei”—“Work sets you free”—marks the entrance.

One of the first things many prisoners noticed upon arrival was the presence of music. A camp orchestra, composed of inmates, was stationed near the gate. Under SS orders, the musicians played as new arrivals entered and as work details marched in and out each day.

The orchestra served several purposes: it was meant to maintain order, create a sense of routine, and in some cases, to mask the sounds of camp life. For those arriving, the sound of music in such a setting was unexpected—adding to the confusion and emotional strain of their first moments inside the camp.

These early impressions—orderly surroundings, barbed wire, a slogan over the gate, and the sound of music—were part of a system designed to disorient and control from the very beginning.

Auschwitz I was the first camp established in what would become the Auschwitz complex. Originally, it was not designed as a death camp but as a concentration camp to imprison political opponents of Nazi rule—primarily Polish resistance members, intellectuals, and others deemed a threat to German occupation.

The site was chosen because of its existing infrastructure. It had been a Polish army barracks before the war, with rows of sturdy brick buildings that made it relatively easy to convert into a prison. The layout was compact and symmetrical, with blocks arranged in neat rows, surrounded by electric fencing and guard towers. Each block served a different function—some housed prisoners, others were used for administration, storage, or punishment.

As the war progressed, the camp's purpose expanded. The Nazis began using Auschwitz I not only for incarceration but also for forced labor, medical experiments, and eventually, murder. A small gas chamber and crematorium were added in 1941, and the camp became a testing ground for the killing methods that would later be industrialized at Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

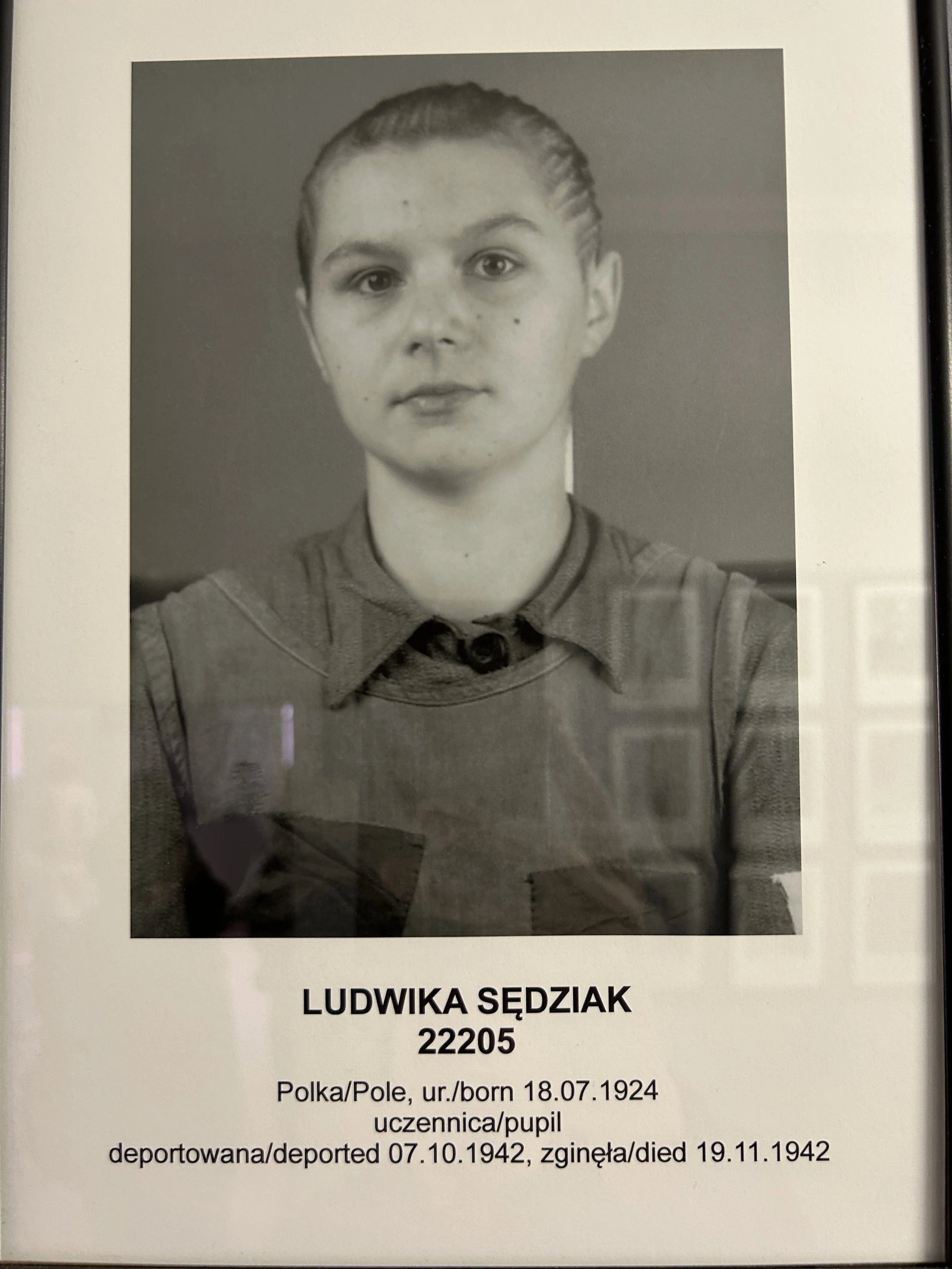

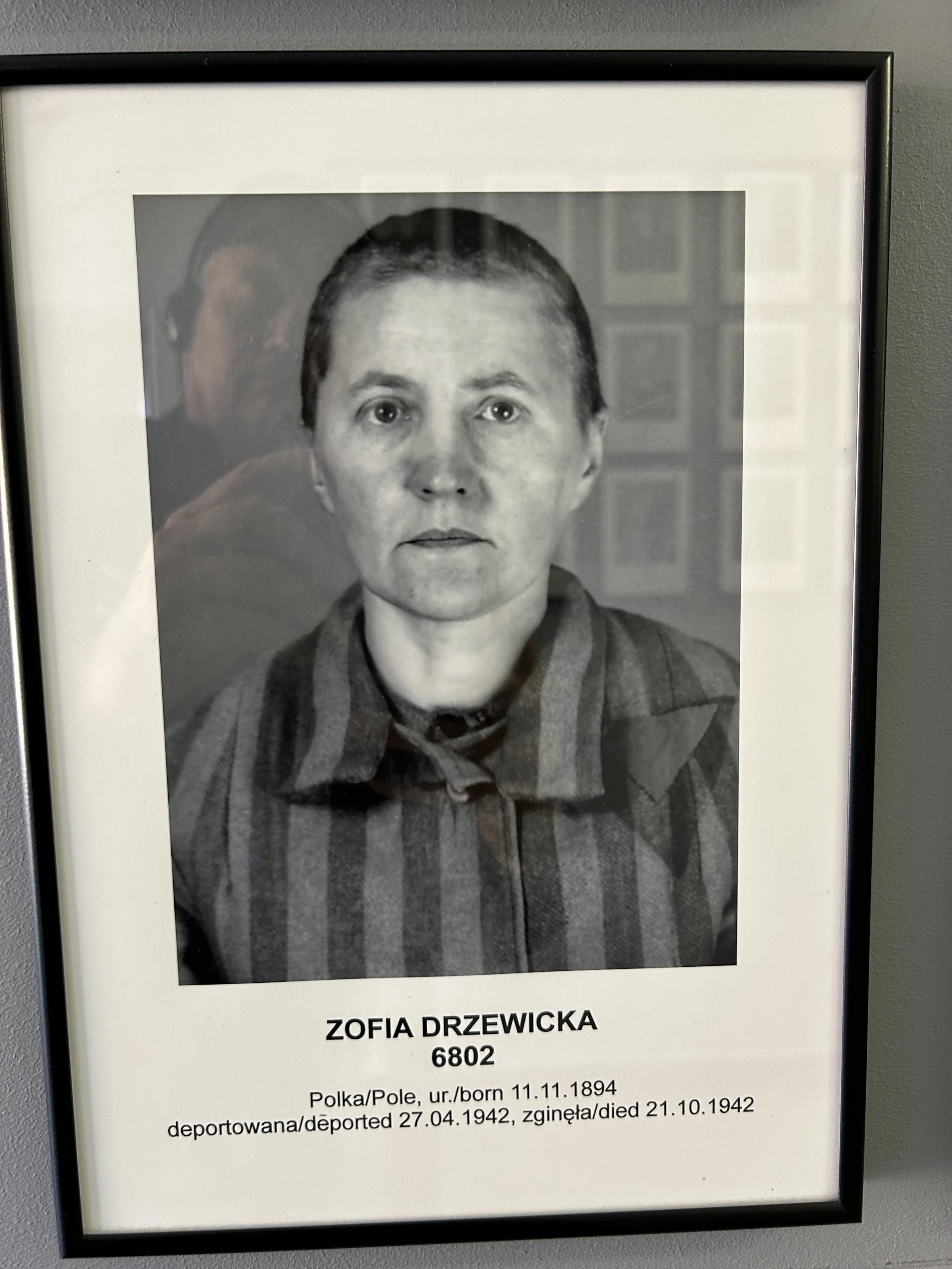

Although Auschwitz I was smaller than Birkenau, it played a central role in the administration of the entire camp complex. It was here that many prisoners were first registered, shaved, photographed, and stripped of their identity before being sent to labor or to their deaths.

Today, the rows of brick barracks still stand—each one holding a different part of this history. Walking through them offers a glimpse into how a place originally built for soldiers was turned into a tool of oppression and terror.

Block 3

Block 3 was one of the many barracks at Auschwitz I used to house prisoners in the early years of Auschwitz !. Originally built as part of a Polish army barracks, it was repurposed by the Nazis as overcrowded living quarters. Inside, prisoners slept in wooden bunks, often crammed several to a bed, in cold, unsanitary conditions. It was here that thousands endured long nights after forced labor, illness, and violence. Gas chambers for disinfecting clothing with Zyklon B were located upstairs in Block 3 and you can still see the blue residue surrounding the vent and door frame. It was not long until the Germans began using Zyklon B as their method of choice to murder millions in the neighboring Birkenau Camp.

Block 5

Block 5 of Auschwitz I, titled “Material Evidence of Crime”, stands as a haunting testament to the lives extinguished during the Holocaust. Within its walls, a vast collection of personal belongings—confiscated from prisoners upon arrival—are meticulously displayed, each item echoing the individual stories of those who once possessed them.

Suitcases with Names

One of the most poignant exhibits features a large glass case filled with suitcases, each bearing the names and birthdates of their owners. These inscriptions, often written in bold letters, were meant to help prisoners reclaim their belongings after "resettlement." The presence of labels like “Waisenkind” (orphan) underscores the tragic fate of countless children who perished in the camp.

Mountains of Shoes

Another striking display showcases thousands of shoes piled high, a somber reminder of the vast number of lives lost. Among the predominantly gray and deteriorating footwear, a few red children's shoes stand out, evoking the innocence of the youngest victims.

Artificial Limbs and Crutches

A separate exhibit presents a collection of prosthetic limbs and crutches, items that belonged to disabled individuals deported to Auschwitz. Their presence serves as a stark reminder of the Nazis' ruthless policies, which targeted not only Jews but also those with physical disabilities.

Everyday Personal Items

The exhibition also includes everyday items such as eyeglasses, shaving brushes, toothbrushes, and kitchen utensils. These personal effects, stripped from prisoners upon arrival, highlight the abrupt and brutal severance from their previous lives.

Hair

(No photographs were taken out of respect for the victims.) The most haunting display in Block 5 is the collection of two tons of human hair, collected from victims after their death in the gas chambers. The Nazis viewed victims’ bodies as raw material and an additional form of monetization. Human hair was sent to factories in Germany to be woven into industrial textiles.

Each artifact in Block 5 serves as a silent witness to the atrocities committed at Auschwitz. Together, they form a powerful narrative that honors the memory of the victims and underscores the importance of remembrance.

“Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed.”

— Elie Wiesel, “Night”

Block 10

Block 10 of Auschwitz I is one of the most infamous buildings in all of Auschwitz, known primarily for the horrific medical experiments carried out on prisoners—especially women—under the direction of Nazi doctors, most notably Carl Clauberg and Horst Schumann. The block was sealed off from the rest of the camp and turned into a site of torture under the guise of science.

Physical Setup and Isolation

Block 10 was directly adjacent to Block 11, the camp’s feared "death block" where punishments and executions were carried out. Block 10 was heavily restricted, surrounded by high walls and guards. Its windows were bricked up or covered to prevent anyone from seeing in or out. Prisoners sent there were completely isolated.

Victims: Mostly Women

The vast majority of victims in Block 10 were Jewish women, many from Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. Some Romani women and other ethnic groups were also experimented on. Prisoners were often chosen specifically because they were healthy and of childbearing age—ideal candidates for Nazi "racial science" research.

Main Types of Experiments

1. Sterilization Experiments (Carl Clauberg)

Clauberg injected chemical irritants directly into the cervix and uterus, aiming to block the fallopian tubes.

These procedures caused unbearable pain, inflammation, internal burns, and many victims died from sepsis or were later killed when deemed "no longer useful."

Women were often forcibly restrained and given no anesthetic.

"The pain was like fire inside my belly. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t scream. They didn’t care." — Anonymous survivor (testimony archived by Yad Vashem)

2. X-Ray Sterilization (Horst Schumann)

Men and women were subjected to intense X-ray exposure to their reproductive organs.

The purpose was to test mass sterilization techniques.

Victims experienced burns, sterility, infections, and cancers. Many were later castrated for "scientific examination" of tissue damage.

3. Artificial Insemination

Clauberg also attempted grotesque artificial insemination experiments, using sperm from SS men or animals. These "procedures" were neither scientific nor consented to, and were more akin to sexual torture.

Other Atrocities

Infectious disease studies were conducted by deliberately exposing prisoners to typhus, tuberculosis, and other diseases to study their effects or to test vaccines.

Victims were often murdered after experiments to allow autopsies.

The test subjects were marked and tattooed with special numbers to track them.

Many died in agony, while others were executed by lethal injection once they were no longer of use.

The Fate of the Victims

Most victims of Block 10 did not survive. Some who were mutilated or rendered infertile were later transferred to the gas chambers or shot in Block 11’s courtyard. Others died slowly from infection or trauma. Only a few managed to live and later testify to the horrors.

Out of respect for the victims, Block 10 is closed to the public.

Block 11

Block 11 of Auschwitz I, known as the “Death Block,” was the beating heart of terror within the camp—a place of silence, screaming, and shadowed cruelty. Its brick walls absorbed the agony of thousands, and even today, the air feels heavier inside. This building, outwardly unremarkable, was where the SS conducted torture, executions, and punishments in the most cold-blooded and ritualistic fashion.

The Entrance to Hell

Prisoners who were marched to Block 11 knew that they might never return. The block is located in the central part of the camp, adjacent to the gravel courtyard where executions by firing squad were carried out. It was surrounded by walls and barbed wire, its windows blacked out with shutters to ensure no one could see in or out.

The very architecture of Block 11 was meant to break the human spirit.

“The Courtroom”: Summary Justice

On the upper floor, the Gestapo Summary Court operated. Prisoners would be tried in sham trials, often lasting no more than a few minutes. These were formalities—death was almost always the outcome.

"You are sentenced to death by shooting," the SS judge would announce with mechanical indifference.

Torture in the Basement

The basement of Block 11 is the stuff of nightmares. It consisted of a series of cells used for extreme punishment. These were no ordinary prison cells—they were designed for suffering:

Standing Cells

Four prisoners were forced into a single, pitch-black cell measuring about 1 square meter (3x3 feet), too small to sit or lie down. They had to stand—all night. These cells were used for prisoners considered “disobedient,” sometimes kept in them for days or weeks. In the morning, they would be marched to work and then returned to the cell. Many collapsed and died from exhaustion, suffocation, or despair.

Dark Cells

These were completely sealed rooms with no light or ventilation. Prisoners were locked inside to suffocate, deprived of oxygen. Sometimes, they were given neither water nor food. Death was slow, silent, and terrifying.

The First Mass Gassing

Block 11 was also the site of a gruesome experiment that would scale into genocide. In the basement in 1941, Zyklon B was first tested on Soviet POWs and Polish prisoners—the first experimental mass gassing in the camp. Hundreds died in one night as the gas filled the airless space, paving the way for the vast machinery of extermination in Birkenau.

Psychological Terror

Even prisoners who were not executed suffered psychological torment. Block 11 was where prisoners were taken for:

Interrogation under torture

Starvation punishments

Mock executions

Witnessing the deaths of others as a warning

The knowledge that Block 11 awaited anyone who stepped out of line helped maintain an atmosphere of fear throughout the entire camp.

Today

Today, Block 11 stands preserved as a silent memorial. The cells remain intact, the Wall of Death still standing. Visitors can walk through the basement, see the standing cells, and feel the oppressive weight of what occurred there. It is not just a building—it is a crime scene, a mausoleum, and a warning.

Block 11 was not only where people died—it was where the SS refined how to erase dignity, how to destroy a human being before killing them. It is among the most powerful reminders of the depths of cruelty human beings are capable of—and of the enduring need to remember.

“In the corridors on the ground floor as well as those in the underground bunkers of Block 11, there was an almost constant racket, created by the opening of cell doors and the conversations among the SS, including the yells and screams of prisoners, emanating from various cells. They were being brought from nighttime interrogations as well as led away during the day so that their sentence could be carried out: 'to the gas,' to be shot or hanged.”

— Boleslaw Staron, Former Auschwitz prisoner

The Wall of Death

This was a dark, wooden wall, designed to absorb bullets and blood, set up as a backdrop for executions by firing squad. Thousands of prisoners were led out from the basement of Block 11, stripped of clothing, and lined up in front of this wall to be shot in the back of the head or neck. The wall was specifically constructed to muffle sound and conceal splatter, part of the Nazis’ systematic efforts to mechanize killing and silence resistance.

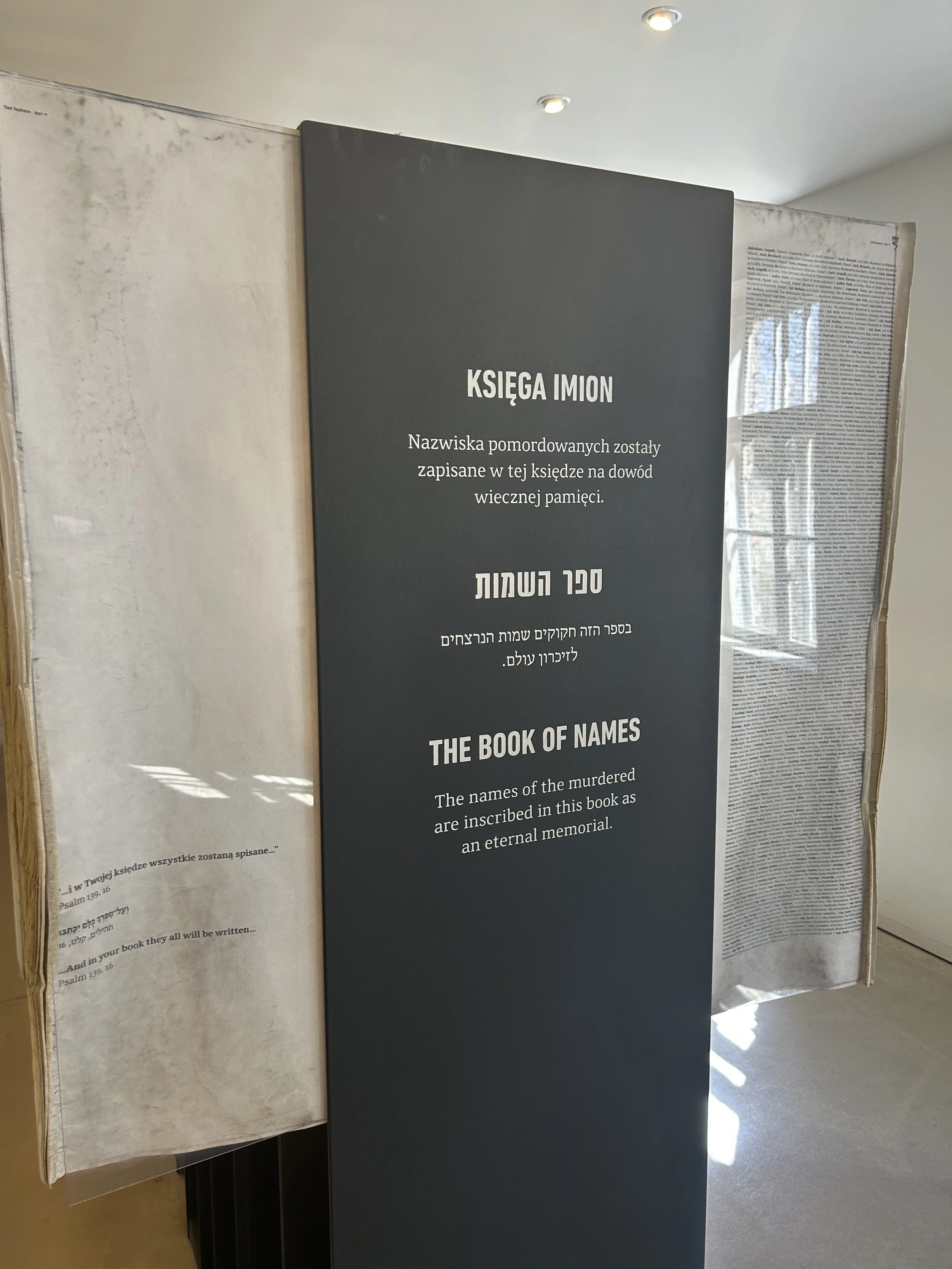

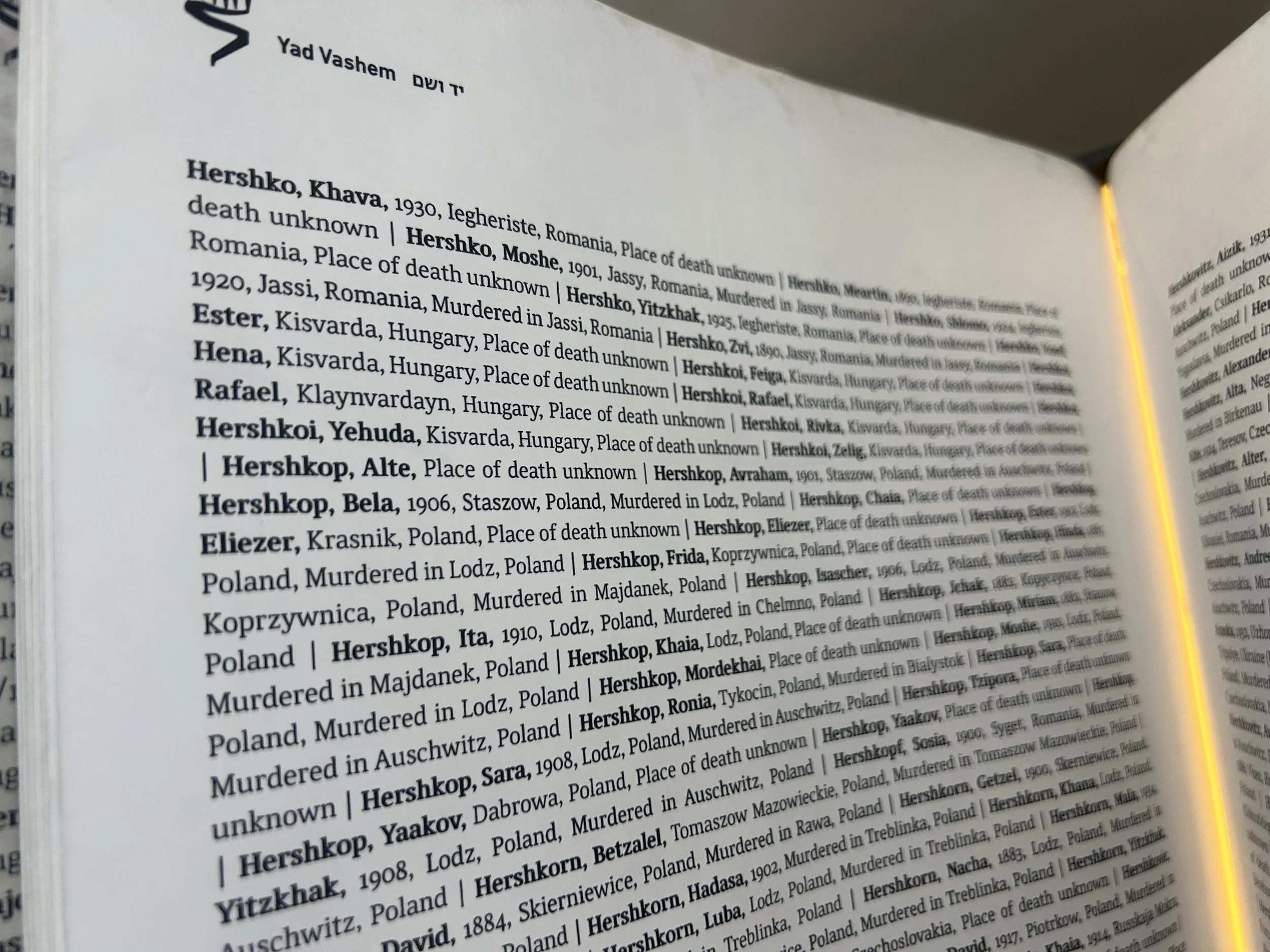

The Book of Names

“You did not live through Auschwitz. The place itself is death.”

— Henri Kichka (1926–2020), Auschwitz survivor

The gas chamber in Auschwitz I, known as Crematorium I, was the site of early mass killings using Zyklon B before the construction of larger extermination facilities at Birkenau. Located just beyond the camp’s main gate, the building originally served as a morgue before being converted in 1941 for gassing prisoners—primarily Soviet POWs and Polish inmates. After 1943, it was decommissioned and partially dismantled by the SS. Following the war, the Polish authorities restored the structure, reopening the gas introduction holes in the ceiling and reconstructing parts of the crematory ovens using surviving original materials. Today, it stands as a solemn memorial—a partially reconstructed but historically accurate space intended to convey the reality of the camp’s function as a site of industrialized murder.

This home inspired the film The Zone of Interest (2023), directed by Jonathan Glazer.

The film is a chilling portrayal of Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz, and his family, who lived in a villa just outside the camp's walls, separated by a garden and a concrete fence from the site of mass murder. What makes the film especially haunting is its focus on the banality of evil—how the family maintained a seemingly idyllic domestic life while genocide occurred just beyond earshot. The photograph below was ironically taken from the site of Hoss’ eventual execution (see below).

Rudolf Höss, the notorious commandant of Auschwitz, was captured by British forces in March 1946 after months in hiding. He later testified at the Nuremberg Trials, where he admitted to overseeing the murder of over a million people at Auschwitz, offering chillingly detailed accounts of the camp’s operations. Extradited to Poland, Höss was tried by the Supreme National Tribunal in Warsaw, found guilty of crimes against humanity, and sentenced to death. In April 1947, he was hanged just outside the gas chamber of Auschwitz I—at the very site where he had overseen mass murder—bringing a measure of justice to one of history’s most heinous perpetrators.

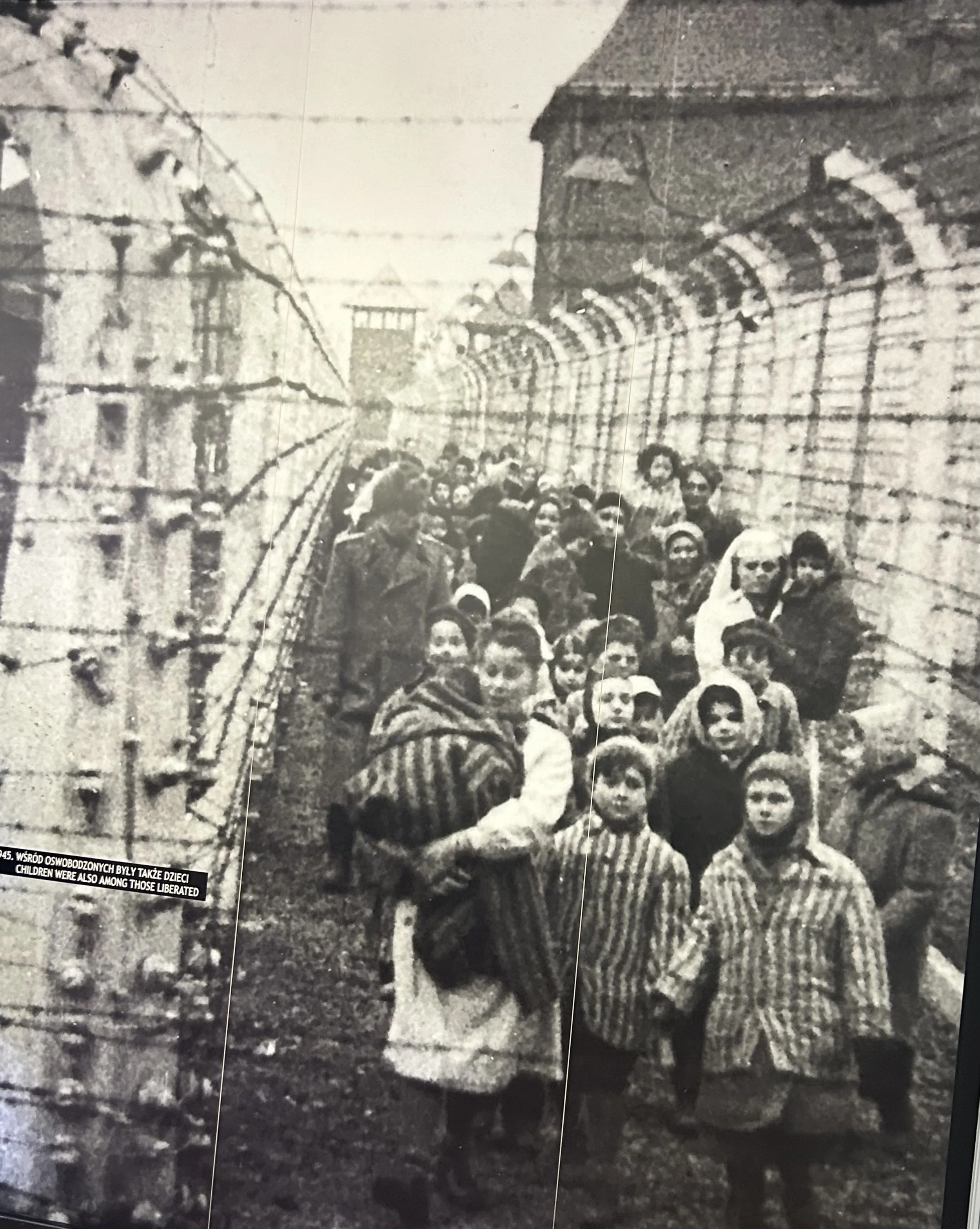

Liberation

Auschwitz III - Monowitz

Monowitz, also known as Auschwitz III, was a Nazi concentration and labor camp established in 1942 near the town of Monowice, just outside the main Auschwitz complex in occupied Poland. It was constructed to supply forced labor to the German chemical conglomerate IG Farben, which was building a massive synthetic rubber and fuel factory known as Buna Werke. The camp held tens of thousands of prisoners—primarily Jews deported from across Europe—who were subjected to inhumane working conditions, starvation, beatings, and medical neglect. Many died from exhaustion, while others were selected for execution when they could no longer work. Monowitz was the first concentration camp built explicitly to serve the needs of a private corporation, making it a powerful symbol of the intersection between industrial enterprise and the atrocities of the Holocaust.

Unlike Auschwitz I and Birkenau, the Monowitz camp no longer exists in its original form. After the war, the site was largely dismantled, and today there are few visible traces of the camp itself. The Buna chemical plant was eventually taken over and repurposed by Polish industry, with parts still in use today. Although there is no preserved museum at Monowitz, memorial plaques and documentation efforts recognize its history. The destruction of the physical camp stands in stark contrast to the lasting impact of its role in the Holocaust and the broader system of exploitation and genocide orchestrated by the Nazi regime.

Auschwitz-Birkenau

The Nazis constructed Auschwitz II–Birkenau to facilitate the mass extermination of Jews and other targeted groups as part of the "Final Solution." The original Auschwitz I camp lacked the capacity for the scale of killings the Nazis intended. Birkenau, located in the village of Brzezinka, was built to address this need. It featured extensive facilities, including four large crematoria with gas chambers, enabling the Nazis to murder thousands of people daily. This expansion allowed Auschwitz to become the largest and most lethal of the Nazi extermination camps.

The original rail station used for deportations to Auschwitz was located just outside the camp complex. When Auschwitz I was first established in 1940, prisoners were brought to this main railway station, which lies about 2–3 kilometers from Auschwitz II–Birkenau. From there, they were marched or transported by trucks to the camp—a process that became increasingly inefficient as the scale of deportations grew.

“We had learnt of our destination with relief: Auschwitz, a name without significance for us at that time, but it at least implied some place on this earth. We had expected something more apocalyptic. It was a labor camp. A factory, they said. But we soon realized what Auschwitz really meant.”

— Primo Levi, Italian Jewish chemist and author of “Survival in Auschwitz” (also known as “If This Is a Man”)

Entrance to Birkenau

“Through the steam, I saw a sign: ‘Auschwitz.’ I didn’t know what it was, but a minute later, I found out.”

— Elie Wiesel, Night

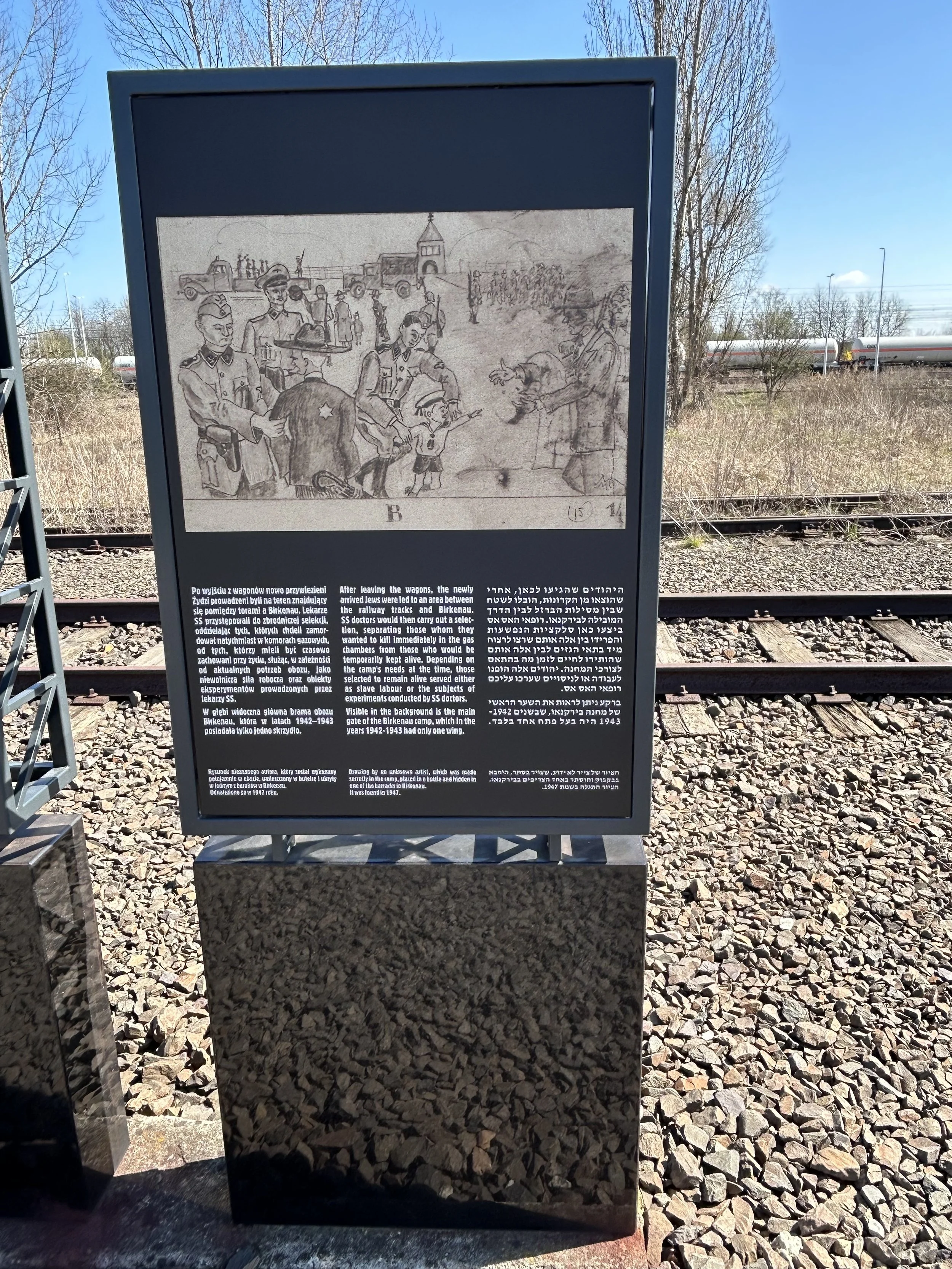

The Selection Process

New arrivals to Auschwitz-Birkenau were herded off the cattle cars and lined up in rows: men on one side, women and children on the other. SS doctors, most notoriously Dr. Josef Mengele, conducted quick visual inspections and pointed left or right. One direction meant forced labor, often a temporary reprieve. The other—usually for children, the elderly, the sick, and mothers with young children—meant immediate death in the gas chambers. The entire process took just minutes, and many victims did not know they were being sent to their deaths.

Upon arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau, women with young children, the elderly, the sick, and others deemed “unfit for labor” were typically sent to the left during the SS selection process. This direction led them, unknowingly, to the gas chambers. The path they walked was deliberately designed to appear non-threatening—lined with trees and bushes, sometimes referred to by survivors as the “road to the showers.” There were no signs or indications of the horrors ahead, and many believed they were going to be disinfected or temporarily housed.

“We stood at the gates of hell. There were guards everywhere, and the air was filled with shouting, barking dogs, and the smell — that unforgettable smell of burning flesh… We arrived. And suddenly we were no longer people. We were numbers, naked and shorn, alone in a place where even time had been destroyed.".”

— Olga Lengyel, Hungarian Jewish survivor and author of “Five Chimneys”

“They walked in silence, their faces marked by resignation, dread, and disbelief. Mothers held their children tightly, some whispered prayers, others sang lullabies… It was as though they wanted to protect their little ones from the horror that awaited them, even as they approached death.”

— Filip Müller

What struck me the most about Auschwitz was how idyllic and peaceful it was.

In the areas surrounding the Crematoria were beautiful grassy wooded areas and clearings. This was intentional on the Nazis part. Once the families (mostly mothers and their children) arrived in these areas, it conveyed a sense of calm. It appeared to be a serene area for them to gather and wait for processing into the Camp. Sadly, it would be the last moment of peace in their lives.

Kanada

The Kanada area of Auschwitz was a special section of the camp where belongings taken from prisoners—especially those murdered upon arrival—were sorted, stored, and processed. The name “Kanada” was ironically chosen by prisoners, referring to the country Canada, which symbolized wealth and abundance in their minds. When new transports arrived, victims were stripped of all possessions, including suitcases, clothing, jewelry, food, and valuables. These items were sent to the Kanada warehouses, where selected prisoners (mostly women) were forced to sort and pack them for shipment to Germany. While the work was physically exhausting and morally wrenching, Kanada was seen as one of the "better" work details because prisoners there had occasional access to food and clothing from the stolen goods. However, it also served as a stark and tragic reminder of the systematic plundering that accompanied genocide.

Crematoria (Gas Chambers)

Crematoria II-V

Crematorium I was located at Auschwitz I. Crematoria II through V were the primary killing facilities at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II) and were central to the Nazi genocide. Built between 1942 and 1943, these four buildings were equipped with underground gas chambers and above-ground cremation ovens designed for mass murder on an industrial scale. Victims, mostly Jews deported from across Europe, were led into what they were told were showers. Once the doors were sealed, Zyklon B, a cyanide-based pesticide, was released through openings in the ceiling or walls. After death, Sonderkommando prisoners were forced to remove bodies, extract valuables like gold teeth, and burn the corpses in large ovens or open-air pits when the crematoria could not handle the volume. These buildings were capable of killing thousands of people per day and were the most deadly facilities in the camp system.

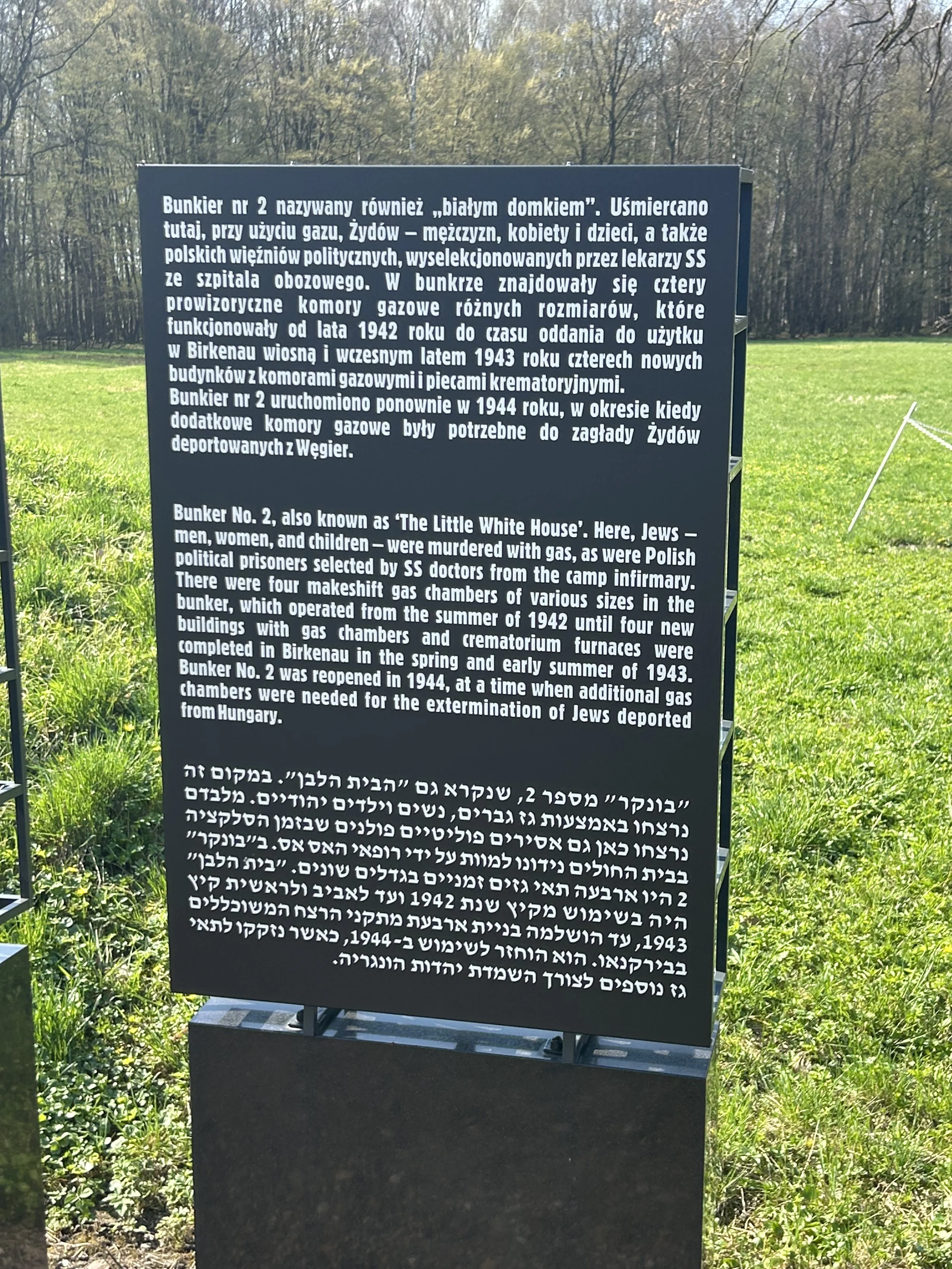

The Little White and Red Houses

Before the construction of Crematoria II–V, the Nazis used two converted farmhouses as makeshift gas chambers: the Little Red House (Bunker 1) and the Little White House (Bunker 2). Located in a secluded part of Birkenau, these buildings were adapted in 1942 to accommodate the growing number of deportees during the early phases of mass murder. Victims were gassed in these primitive structures using Zyklon B, and the bodies were initially buried in mass graves or later burned in open-air pits. Though more rudimentary than the later crematoria, these bunkers played a key role in the transition from sporadic killings to a systematized process of extermination. They continued to be used intermittently even after the larger crematoria became operational.

As the war neared its end and the Soviet Army advanced toward Auschwitz in late 1944 and early 1945, the Nazis began systematically destroying evidence of their crimes. This included efforts to dismantle and blow up the crematoria and gas chambers, particularly at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Crematoria II and III were blown up in January 1945 by the SS, just days before the camp's liberation, while Crematorium IV had already been damaged earlier during a prisoner revolt in October 1944. Crematorium V was also destroyed around the same time. They also burned documents, exhumed mass graves, and forced prisoners to remove or incinerate bodies in an attempt to hide the scale of the genocide. Despite these efforts, enough physical remains, documents, and survivor testimony endured to expose the full scope of the atrocities committed at Auschwitz.

Creamtorium II

Crematorium III

Crematorium V

The Little White House

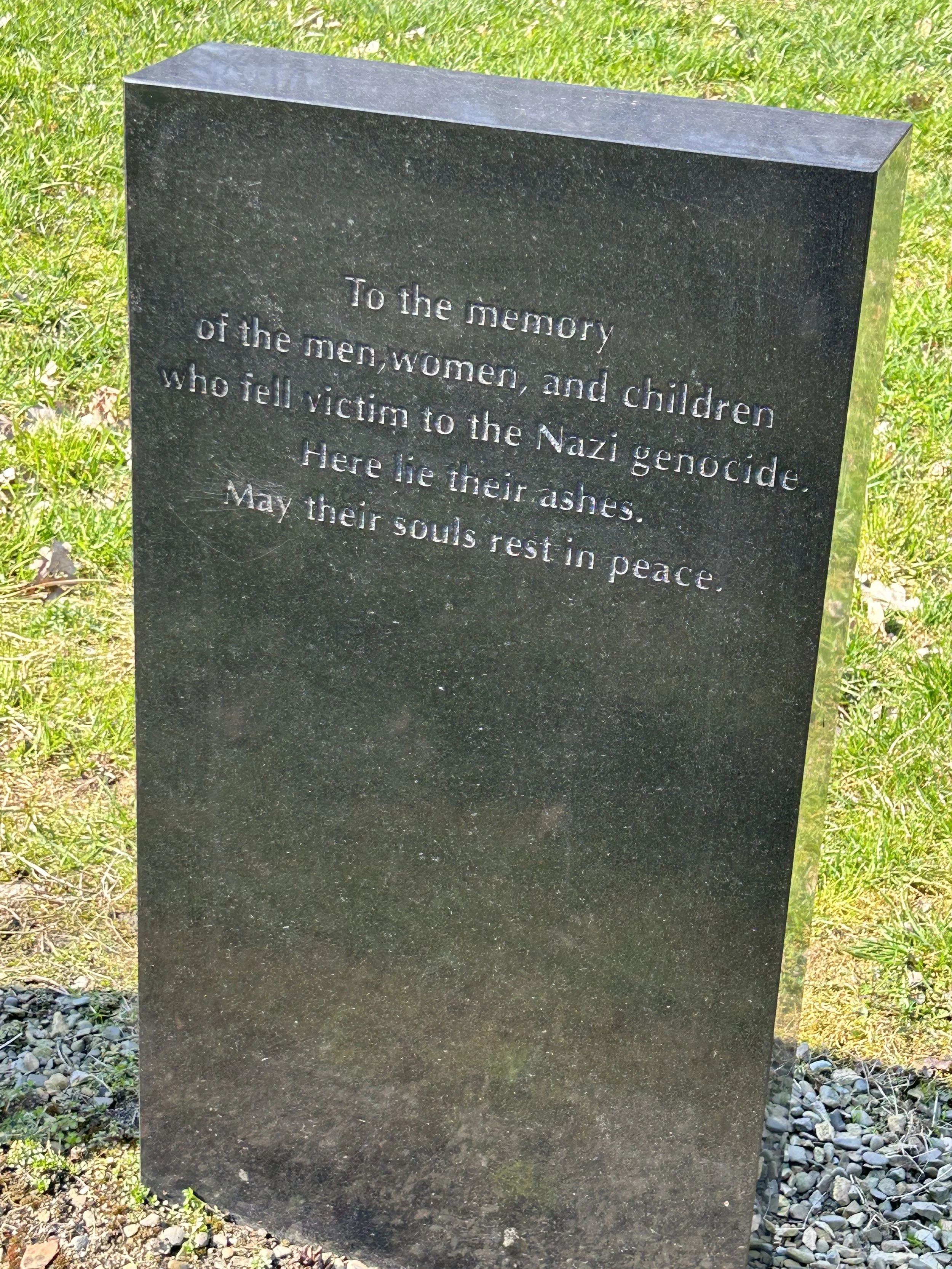

Auschwitz-Berkenau is the largest cemetery in the world. The remains of over 1.1 million people lie at rest on the grounds of the Memorial.

The Nazis had several areas outside the Crematoria where they either burned or buried their victims. These areas are each marked with memorials.

Her Story.

One Day in Auschwitz is a poignant 2015 documentary produced by the USC Shoah Foundation and directed by Steve Purcell. The film follows Holocaust survivor Kitty Hart-Moxon as she returns to Auschwitz-Birkenau 70 years after her liberation. Accompanied by two teenage girls the same age she was during her internment, Kitty shares her harrowing experiences and the daily struggle for survival in the camp. The documentary delves into themes of resilience, the importance of remembrance, and the transmission of history to younger generations.

“The Banality of Evil”

The "banality of evil" is a concept introduced by political theorist Hannah Arendt in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963). Arendt developed the idea while covering the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a key Nazi bureaucrat who organized the logistics of mass deportations to extermination camps during the Holocaust.

Arendt observed that Eichmann was not a fanatical, monstrous figure, but rather a mundane, ordinary man who claimed he was simply "following orders" and doing his job. The "banality" refers to the disturbing normality and thoughtlessness with which horrific crimes can be committed—not by sadistic villains, but by average individuals who fail to think critically about their actions or the moral consequences of their obedience.

The phrase challenges the idea that evil always stems from deep hatred or extreme ideology. Instead, it suggests that evil can be carried out by ordinary people who conform, obey, and do not question unjust systems—making it all the more dangerous.

Outside of Birkenau are the remains of the railroad tracks that once carried 1.1 million human beings to their death, and thousands more to unspeakable suffering. These tracks are now overgrown with weeds and brush. The disappearance of the tracks is a metaphorical warning to us all that as time passes, the memories of what happened at Auschwitz and Treblinka, Belzec, Sobibor, Chelmno, Majdanek, and thousands of other Nazi camps has begun to be covered and obscured by the brush and weeds of time.

We all have a duty and obligation to never let that happen.